Why Is DCF So Complicated?

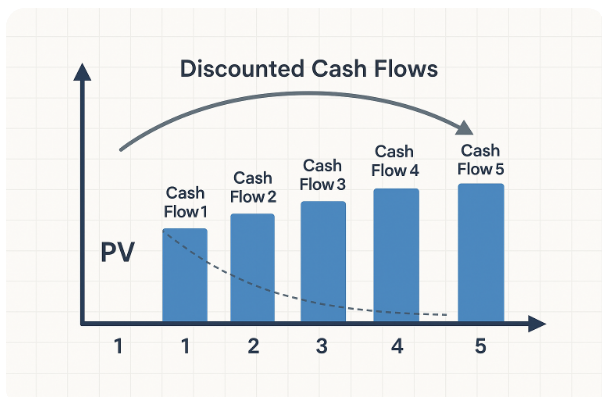

Discounted cash flows (or DCF) is a technique that can help determine the value of a firm based on it’s cash flows discounted with a rate of return required by investors. This rate of return is often the source of stress for novice investors. In this article, we’ll discuss some shortcuts that you could take (much to the chagrin of diehard DCFers) but I am going forth with it anyway. It’s my article and I can do what I want.

My beligerence aside, in all seriousness, I feel like we can make some assumptions based on some of my DCF observations. I really believe that there are two assumptions that we can fiddle with and still come up with a decent model. The two assumptions that we can work with are:

- The discount rate

- The Terminal Value (TV)

But before we get into these tweaks, let’s first discuss the motivation behind discounting cash flows.

Why Do We Need to Discount Cash Flows?

If you’ve ever studied bonds, the price is essentially derived from the cash flows. There is a lot that is unsaid here, in that, not all bonds are created equal and won’t be valued as such. But let’s focus on a standard coupon-paying bond.

When you buy a bond, you pay a certain price (usually the face value plus any premium or discount) based on the prevailing interest rates. We have these interest rates to account for the time value of money (TVM). I am not going to go too in depth with this concept (and I linked to a good resource). But in a nutshell, the TVM states that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar sometime in the future.

Why?

Because you can invest that dollar today and based on the return of the investment, it will be worth more in the future. If you don’t invest properly, it’s possible that the future value will be lower than the dollar today, but that is another issue entirely. The TMV assumes that the investment will rise. And over time, it usually does.

Just like bonds, companies have cash flows generated from the operations of the business. But unlike bonds, there is no guarantee by the board of directors of the stocks you own that you will see a steady stream of cash flows (unless the company pays dividends – again topic of another conversation.)

Companies often retain the profits that they earn so that they can generate even bigger profits in the future. If they are successful (and many are not), you may see an increase in the profits again (and hopefully again after that).

As you may know already though, stocks are inherently more risky than other asset classes, like investment grade bonds and government securities. Therefore, companies will require a higher return on their investments than alternatives like bonds or money markets. This is a crucial concept in the DCF.

Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC)

This is the item that tends to trip people up when dealing with the DCF. The DCF calculations are usually pretty easy but people tend to struggle with what discount rate and that is what is associated with WACC.

Instead of getting lost in complicated WACC formulas, I use a simple, volatility-based approach that’s quick, reasonable, and fits most real-world cases.

As mentioned, WACC stands for Weighted Average Cost of Capital, which is just a fancy way of saying the average return a company needs to pay its lenders and investors. Instead of getting bogged down in the math behind this, you can use a shortcut by looking at how volatile the stock is. If the stock has a low beta (under 1), a WACC between 7.7% and 8.5% usually works. If beta is around 1, figure 8.5% to 10%. And for really jumpy stocks with high beta, you’ll want to use 10.5% or higher. It’s a simple way to keep your valuation grounded without overcomplicating things.

People who have painstakenly learned how to actually calculate the WACC will probably be the ones to take exception with my shortcut. I’m okay with it. I feel it’s defensible in that if you checked on Chat GPT or other places that can give you the most recent WACC for the company in question, you’ll see that I am close.

What About Terminal Value (TV)?

In most classical definitions of DCF, the TV can be calculated using a formula. My issue with this is it often inflates the DCF calculation, even to the point where you’ll never get to a valuation that comes close where it should be.

I viewed a Udemy training where the instructor kind of touched on this issue. He said to just keep projecting out to 30 to 35 years. Many firms won’t last for that long and ones that do will likely be acquired or merged.

To me, this logic makes sense and to further this, in my book, if a company merges, is acquired, or goes out of business, you should record the number of years that it was in business prior to those events.

I had Chat GPT do a kind of informal analysis of companies where these events were triggered and asked it to go back to the 1960s to get a good cross section of companies that could be used to validate my suspicions. The analysis led to about a 36+ year average of companies. So that’s in-line with the 35 years the instructor suggested.

Conclusion

If you ascribe to this way of thinking, then your DCF analysis just got a whole lot easier. You have your discount rate, you keep going with your projections of cash flows to 35+ years (you can go higher if you like), and you now can get a discount factor for all your cash flows and just add them up.

Yeah, it really can be that simple.

Let me know if you want me to produce an example of this for the next article.