How Much Accounting Knowledge Do You Need to Invest?

Accounting is the language of business. Warren Buffett states that if you aren’t willing to learn the principles of accounting, you have no way of learning how a company is doing. While it’s true that the more accounting you know, the better, it’s not necessary to be a CPA to become an investor. Besides, accounting takes time to learn. Investors should have a grasp of a few concepts during their start, and that is what this article is about.

Accounting is a subject that you either love or hate. People who are meant to be accountants seem as though they are born to it. They love numbers, and they get enjoyment from reading pages of financial reports. For everyone else, accounting is a downright chore.

The best way to begin is to learn about ratio analysis. The advantage of doing this is you can spot trends over time.

A company’s prime money-making entity is its assets. When individuals think about assets, they don’t think about them in terms of how much money they will help them make. For instance, when a household buys a television, it’s not with the intent to learn what the return on investment for that component will bring to the family. They buy it for pure enjoyment.

A company must think in terms of how well the assets it acquires will help it grow its business. The better the earning capabilities of these assets, the more significant an economic advantage the firm will enjoy. Investors need to get a handle on whether their potential companies are choosing the right assets for the earning engine to hum. Once armed with this knowledge, investors have the advantage of selecting firms with the lowest opportunity costs, i.e., the ones whose assets will generate significant income over the ones that will flounder.

Assets

One measure to determine how a company is doing with its assets is the Asset Turnover Ratio (ATR). This ratio takes the sales during a given period and divides it by the total assets for that period. Investors should look for high turnover ratios, which indicate that a company can use its assets efficiently to make sales.

Like most ratios, it’s better to use the ATR for comparisons, both year-over-year and against other companies in the same industry. Comparison to companies in different industries won’t make as much sense as industries use assets in varying ways across industries.

Debt

Most investors are familiar with the term debt as they likely experienced it personally. Companies borrow money to expand operations. Stable companies that make money will manage their debt levels effectively. Companies that don’t manage their debt effectively will run into serious trouble if they continue those practices.

No matter how debt is used, it creates an obligation to the company to pay back that money. The terms vary between companies and industries. However, at some point, the companies will be expected to satisfy their debt obligations. Companies that fail to do this will either need to declare bankruptcy or go into liquidation. Creditors will have first claims on companies that liquidate.

Investors will have their line in the sand as to what constitutes acceptable debt for the companies they choose. This is something that you will need to determine yourself as an investor.

Some investors accept no debt whatsoever and feel companies that don’t use the tool have staying power. There is truth to this. The trouble for these investors is companies may be capable of servicing the debt at the start of the loan. They become incapable of handling the debt as business conditions change.

To measure debt effectively, investors can use the debt-to-equity ratio. This ratio is also considered to be part of the leveraged ratio family. It’s the one that is used frequently as it indicates how much debt compared to equity the company is using to finance its operations.

The concept is similar to when people buy homes. The house and land are considered the homeowner’s assets. When homeowners purchase the home, they put down a down payment, usually around 20%. This is considered the homeowner’s equity in the house. If a house cost $100,000 to purchase, the homeowner would have $20,000 equity, which leaves $80,000 in debt.

The house example is an oversimplification as most homeowners purchase their homes to live in them. The way to make this example closer to how businesses use and finance assets would be to make the house a rental property. Then, the investors (homeowners) could measure how well their assets (homes) are doing to produce income.

The debt-to-equity ratio is simply the total amount of debt divided by the shareholder’s equity.

The higher the number, the more amount the company is leveraged. While this ratio could be used to compare companies across industries, it’s usually best to make a comparison with companies in the same industry. Different industries have unique requirements when it comes to financing. A capital-intensive firm will likely need leverage to start. Whereas, a service firm, like an internet company, doesn’t need much startup capital.

Price-to-Earnings Ratio (P/E)

Many investors like to use the Price-to-Earnings Ratio (P/E). This ratio is used to determine whether companies are overvalued or undervalued. The cutoff point is usually around 20%, although this varies by industry and by investor. Investors put too much faith in this ratio, which forces them to get out of a stock too soon, or they sit on the fence when thinking of buying. This problem is compounded by digital companies who seem to defy traditional metrics concerning business cycles. Because they outlast the business cycles by a wide margin, you should expect their P/E ratios to be high. The ratio should be treated as a guideline and not and rule.

Disclaimer: There are many ratios that investors use to determine the health and viability of companies. Their uses depend on many circumstances that are too numerous to cover in this article. The two ratios described (ATR and DTE) here are a great starting point for beginners. It is crucial to learn more ratios and investing techniques as you progress with your investing experiences. The two ratios will likely not be enough to determine whether a company is a good investment choice. They can be used as a first-pass filter when screening for companies.

How to Find the Data

You’ll find plenty of resources that publish investing data. One of the best for the purposes of this discussion is Morningstar.com. The service has a free version that publishes at least five years of financial data. Paid subscribers have access to ten years of data at the time of this writing. You should check with your local library as they may have this service as part of its membership.

When searching on Morningstar, you can enter the company name or the symbol. Morningstar will confirm your selection. The first screen that appears will be the quote screen and gives the price of the company with a chart of its price history. You’ll see a list of options directly under the company name. One of those options is the Financials tab. Select that tab, and it will show a summary of a few data items. Under the chart that is displayed is an option to choose All Financial Data. That is the option you’ll want to view.

For our two ratios, you’ll need the Balance Sheet and the Income Statement. These options can be selected underneath the company name and symbol. Find the necessary components and record them in a spreadsheet. You can also download each of the financial statements into a spreadsheet. The format is a file in Comma-Separated Value (CSV) format, which most spreadsheet programs can read easily.

When using the Asset Turnover Ratio, most analysts use an average of the beginning and ending periods. To accomplish this with the Morningstar data, you can use the previous year’s value as the beginning of the current year and average those (beginning + end) / 2. This will be good enough for this analysis.

Don’t Overlook Qualitative Factors

Investors spend a good chunk of their time crunching numbers. While this exercise is useful, it doesn’t give the whole picture of a company’s potential. There are qualitative factors that investors should consider, as well. While this topic is also too extensive to cover in this article, concentrate on reading the Management Discussion and Analysis (MD&A) section. This gives a roadmap by the CEOs of companies. Morningstar won’t have this data. You’ll need to download this from the Security Exchange Commission’s website (SEC.gov). An alternative is to go to the websites of your potential companies. They will have an Investor’s Relation section, which will contain an annual report. Usually, though, these reports are in PDF format. But, if you are using it to read the MD&A, then this format will suffice.

You’ll want to read the entire section as it will give you some guidance on where the company is headed for the year to come. The most significant value of this section measures how well management did from past MD&A reviews. For instance, if a CEO specified in a previous report that the company would expand into Asian markets by 30% and stalled on this initiative, are they explaining this false start in the current MD&A? When you review past annual reports, you can gauge how well management did with their plans.

Another item not to overlook is the footnotes. These are hidden gems that most investors overlook. While there can be valid reasons why management relegates information to this section, it can also indicate inappropriate behavior.

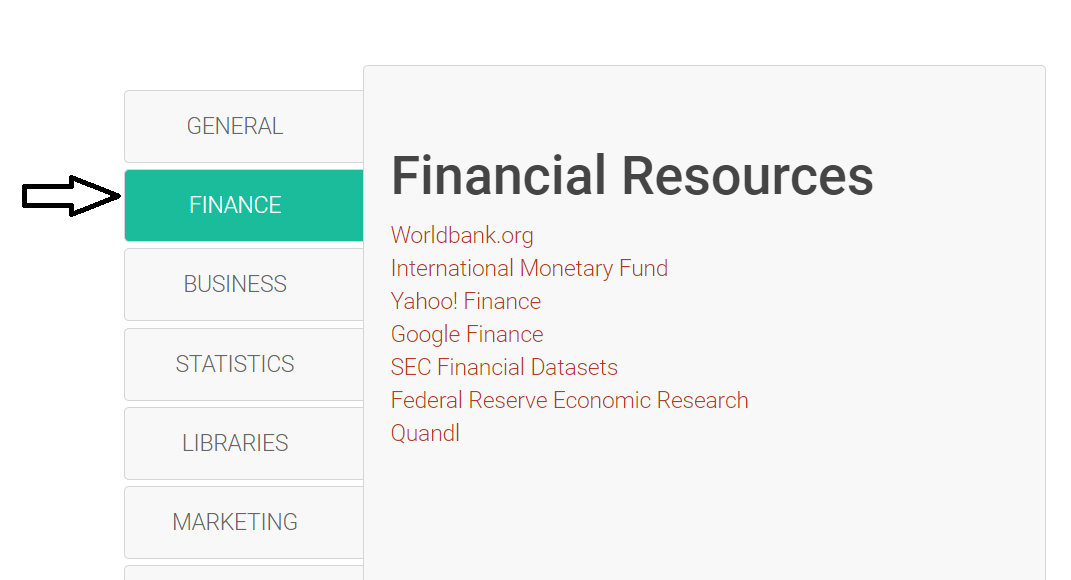

NOTE: On DataScienceReview.com, there is a link for data sources. When you click on the Finance tab, you will see several sources that you can use for your stock research. The SEC website is one of the ones listed. This resource changes from time-to-time, so it may be different when you view it.

Conclusion

Investing is not an easy activity. The operations of companies are complex, and investors must consider the company itself, the industry, the economy, and the geopolitical landscape. However, investors need to start somewhere. The information in this article should serve as a good jumping off point for beginning your investing education. Learning about companies is a never-ending process, and you can expect to make mistakes. But, as you increase your knowledge and experience, you’ll be on your way to reducing those mistakes and recognizing great companies when you see them.