A Few Ways to Invest a Lump Sum of Money

Wouldn’t it be great to get a pile of cash? It doesn’t happen that often, but it pays to know what to do when it does. Many people would be tempted to spend it. However, with the right approach to investing, you can grow that sum significantly. Learn about a few ways to invest a lump sum of money.

Disclaimer: nothing in this article should be misconstrued as investment or financial advice. Please seek the advise of a qualified financial professional.

Related: The Accounting Equation Defined

Pay Your Taxes Due

Certain cash sums will be free of taxes. For instance, many life insurance policies, when taken as a lump sum, are not taxed. Also, settlements from lawsuits often do not generate a taxable event.

For most lump sum payments, you may need to pay taxes. You’ll have to determine your tax bracket. It’s usually a good idea to seek out a qualified tax adviser, as there are too many tax rules for the average person to grapple with.

The takeaway here is to make sure you have enough from the lump sum to pay any taxes due. That’s crucial. If you end up investing the entire lump sum and you have to liquidate some of the investment later to pay taxes, you may suffer losses. These losses can be substantial depending on the amount of taxes due.

To Dollar-Cost Average or Not to Dollar-Cost Average

Traditional investing tips suggest a method called dollar cost averaging (DCA), although it’s not as popular advice as it used to be. The concept is simple. You divide your lump sum into a series of smaller amounts and invest those amounts at regular intervals (monthly, quarterly, etc.) The advantage is you weather volatile movements in the market. When stocks are increasing, you’ll buy less shares of your investments. When stocks are declining, you accumulate more shares.

An article from A Wealth of Common Sense points to research from Vanguard suggesting that during normal markets, dollar-cost averaging can hurt returns. These studies purport that investing the lump sum all at once in an index fund will outperform the DCA strategy.

For instance, if the index is at $1,000 and you have $10,000 to invest, you’ll own 10 units ($10,000 / $1,000) of the index. Suppose after thirteen months (to make the numbers match for both scenarios), the index value increases to $1,600. You’re are sitting on a paper profit of $6,000 ($1,600 x 10 units = $16,000 – initial investment of $10,000).

In the particular year the article was written (2018), the author stated that many companies were overvalued. This suggested that the market was anything but normal. While it took until the end of that year for the market to pull back, it did so rather substantially. In this instance, DCA would have weathered this situation easier than the one single investment or lump sum.

Conversely, if you invested $1,000 per month for ten months, and the price of the index rises by $50 per month, the following would represent this investment:

Month 1: Price for 1 unit = $1,000 – buy one unit

Month 2: Price for 1 unit = $1,050 – cannot buy due to shortage of funds (only $1,000)

Month 3: Price for 1 unit = $1,100 – buy one unit ($900 carried over)

Month 4: Price for 1 unit = $1,150 – buy one unit ($750 carried over)

Month 5: Price for 1 unit = $1,200 – buy one unit ($550 carried over)

Month 6: Price for 1 unit = $1,250 – buy one unit ($300 carried over)

Month 7: Price for 1 unit = $1,300 – buy one unit ($0 carried over)

Month 8: Price for 1 unit = $1,350 – cannot buy due to shortage of funds (only $1,000)

Month 9: price for 1 unit = $1,400 – buy one unit ($600 carried over)

Month 10: price for 1 unit = $1,450 – buy one unit ($150 carried over)

Month 11: price for 1 unit = $1,500 – cannot buy due to shortage of funds (only $1,150)

Month 12: price for 1 unit = $1,550 – buy one unit ($700 carried over)

Month 13: price for 1 unit = $1,600 – buy one unit ($100 carried over)

This is an unrealistic example. Even in good markets, you’ll have price fluctuations to the downside for certain months. Then, you would pick up more shares for less. However, if the above scenario played out for the DCA, it would have cost $3000 more than investing everything at once. Also, you’d have $100 left over as cash, not earning the same rate as the invested amount.

Here is an interesting twist. What if you varied the dollar amount rather than the shares purchased? Instead of accumulating enough money each month to purchase one share (and skipping months when you don’t have enough), you purchase one share every month whatever it costs and subtract from the total. Your total cost would be less than first scenario, by $600. However, you’d have $600 in cash leftover and you would only have eight (8) shares working for you. Both of the previous scenarios would trample this scenario if the market continued rising).

Here is the schedule for this scenario:

Balance = $10,000

Month 1: buy one share at $1,000. Balance = $9,000 ($10,000 - $1,000).

Month 2: buy one share at $1,050. Balance = $7,950 ($9,000 - $1,050).

Month 3: buy one share at $1,100. Balance = $6,850 ($7,950 - $1,100).

Month 4: buy one share at $1,150. Balance = $5,700 ($6,850 - $1,150).

Month 5: buy one share at $1,200. Balance = $4,500 ($5,700 - $1,200).

Month 6: buy one share at $1,250. Balance = $3,250 ($4,500 - $1,250).

Month 7: buy one share at $1,300. Balance = $1,950 ($3,250 - $1,300).

Month 8: buy one share at $1,350. Balance = $600 ($1,950 - $1,350).

As mentioned, the total cost for this scenario is actually less than the first scenario. However, you don’t buy as many shares (only 8).

Either DCA approach may outperform the lump sum investment when the market is volatile. You’ll be able to buy more shares when the price dips. DCA is one of the truest forms of buy low, sell high (although you don’t want to sell until your planned time horizon).

These simplistic examples also assume you are investing in safe stocks. An index of the S&P 500 is generally considered a fairly safe investment because it represents the market. Since many believe that the market is mean reverting, other investments may not do as well in the long term.

Related: Start Investing Even When You Don't Know How

Commissions and Taxes

The above scenarios don’t account for commissions and taxes. Commissions are not as big an issue because many brokers have eliminated them or reduced them significantly. They could, however, reintroduce them in the future.

If you buy and sell often, you can expect to pay a portion of your returns in capital gains taxes. This won’t be as big an issue if you are managing a 401K (until you redeem). But capital gains taxes can add up in regular accounts. Also, it’s difficult to say what the government will do to these taxes in the future. By not overtrading, you won’t have to worry about these issues.

What About Individual Stocks?

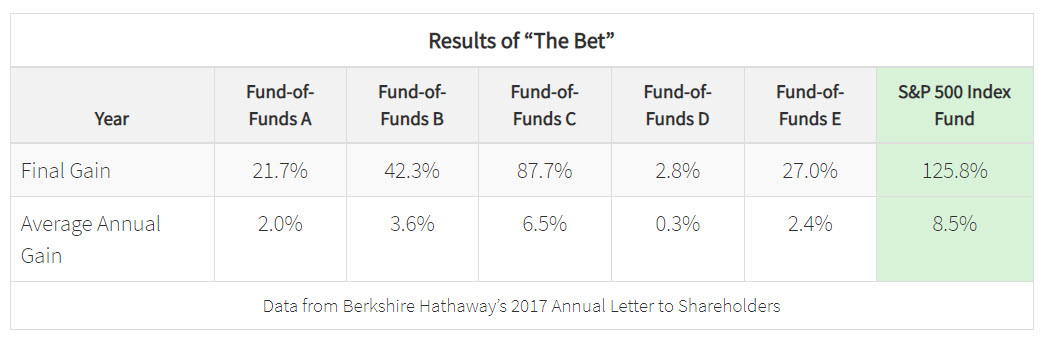

You may have heard about a bet Warren Buffett made with Wall Street companies in 2007. He challenged hedge fund companies to a ten-year bet. Buffett and the challenger (there ended up being only one) would both start out with the same cash amount, but as part of the bet, the hedge fund manager was required to use the average of five hedge funds of his choosing, which represented active investing.

Related: What Are the Risks of Investing in Stocks?

Warren would invest only in the S&P 500 index. This represented passive investing. The challenger didn’t even finish out the bet and conceded a year early, as Buffett won by a landslide.

The takeaway is that passive investing, such as what you get with investing in the S&P 500 via an index fund, will likely beat out most other investments in the long run. Trying to buy shares of individual stocks is going to require much more work on the part of the average investor. This would be an active investing strategy.

Active investing requires evaluating portfolio performance and rebalancing the portfolio when its allocations are no longer in line with the goals of the portfolio. Active trading also requires more trading by its nature.

Unless you are planning on becoming a professional money manager and have the time and financial resources to dig into financial information for eight (or more) hours a day, investing in individual stocks may not be the right approach. It can be done, but too many people don’t perform the proper due diligence. It stems from their mindset. They treat stocks as some mysterious entity they hope will be higher in value sometime in the future. Then, they sell at the wrong time.

This strategy is rife with problems and most often leads to disastrous returns. It’s not to say people cannot succeed with investments in individual stocks. However, stocks should be treated as ownership in a company.

You wouldn’t buy a deli in your local town and expect it to run itself. When you invest in shares of a company, you won’t be responsible for the day-to-day operations. However, knowing as much as you can about the companies you invest will serve you well. Investors who don’t want to commit resources to learning about companies may want to consider index funds.

Index Funds Aren’t Sexy

When people discuss their investments, hardly any of them will mention that they invest in index funds. That’s boring. Index funds simply track a basket of stocks within the index. For the S&P 500, the index fund tracks the 500 companies that comprise the S&P 500 top stocks. The S&P is a benchmark.

Most people who discussed their stocks, usually tell you about their best performers. They conveniently leave out their losses, though. Some investment managers are guilty of this practice, too. It’s a concept called survivorship bias. Suppose a manager touts the performance of their portfolio. They often leave out the poor returns of stocks from a few years ago, because they no longer own these stocks.

Even though index funds are not sexy to discuss, there’s nothing unsexy about their returns. Even if you bought the S&P 500 at the peak in October 2007 (right before the mortgage meltdown), you would still be way ahead today, and that includes the recent market meltdown from the pandemic of 2020.

Most investors consider investing in the S&P 500 a safe bet. Nothing is 100% safe, but if the S&P takes it hit, it means that something more systemic is going on to cause the price to fall substantially. In other words, if the S&P index is falling, you can bet most (if not all) stocks are falling, too.

Related: Challenges When Analyzing Financial Data

What About the Naysayers?

Some investment advisers are warning against investing large sums of money in index funds. These advisers believe that the S&P has run its course. This is just another example why investing decisions are not easy.

Maybe the author (Rob Isbitts) is correct. However, one of the tenants of investing is to hold a diversified portfolio of stocks. That is what the S&P offers. Isbitts may be correct, but who knows? He doesn’t seem to offer up any alternatives. Let’s also remind ourselves of the bet Buffett made. Over the course of ten years, his S&P strategy did just fine and helped him win the bet.

The point is, there are no guarantees with investing. The author does suggest that actively manage your account, which is counterintuitive for index investing. Keep tabs on your portfolio and make adjustments as needed, is the thinking. Once again, he is vague on what adjustments you should make.

I don’t write this to bash the article or the author. In fact, I chose the article as it was the first one I found offering a counter argument. I am glad it was written to help you focus on the risks associated with investing. Isbitts is a wealth advisory manager. It’s in his best interest to convince you of the perils of index funds. The best decisions are made with all information available. Don’t let bias cause you to look for information that supports only your thesis!

Here's an interesting twist. An article from 2009 suggests that the bet made by Buffett wouldn't perform well, even though it was ahead for that year. The author of that article stated that actively-managed funds would surly win out over the long run.

Keep in mind, this article was written while the bet was still going on. I haven't found any information (Yet!) from the author of this article on his opinion about how the bet concluded. I would love to know what he believes now! It's probably something he doesn't want to explore.

For some perspective, the S&P 500 was $16.81 (average) in 1950. If you bought 100 units at that price and held it until today (S&P approximately $3,000 in 2020), you're looking at a return of almost 18,000%. (3000-16.81/16.81). I am going to bet several investment advisers wrote along the way about how the S&P 500 is a poor investment choice.

What About Exchange Traded Funds (ETF)?

The emergence of exchange traded funds (ETF) has changed the landscape for investors. ETFs are like mutual funds but they are traded like stocks. You don’t have to wait until the end of day for the market to determine the Net Asset Value.

Because an ETF is a stock that tracks the performance of a basket of goods, it is similar to index funds regarding safety and potential returns. However, people can use aspects of ETFs that make them less safe.

Because ETFs are traded like stocks, they can be shorted. While I won’t go into the pros and cons of shorting, it is counterintuitive for one looking for safe investments. It almost never has a place in an investment portfolio. One could argue that shorting makes sense for traders (as opposed to investors). However, many traders lose. Just because someone labels themselves as a trader doesn’t mean they make money. Mutual funds do not allow shorting by comparison.

Investors can also trade options on ETFs. An option is a contract that gives the holder the right, but not the obligation, to purchase (or sell) stocks within a specified time for a specified amount. This concept is too complicated to get into here.

Options are what is known as a derivative product, which means they derive their value from some underlying investment. In the case of ETFs, the underlying investment is the ETF itself. The pricing of any derivative product is wickedly complex for the average investor to grasp.

I am not against options, per se, and I have written articles about them. I believe they can be used to enhance a portfolio. When used right, they can be safe. But investors need to know what they are doing.

People who enter the options market and don’t learn everything about it are almost guaranteed to lose. Worse, if they happen to get lucky with a particular options trade, they gain a false sense of security and try to maximize their gains by taking even bigger risks.

If you stay away from shorting and options on ETFs, they can be considered the same as index funds in both terms and safety and return potential. One popular ETF for the S&P 500 is the SPDR (Symbol: SPY, commonly referred to as the Spyder).

Conclusion

People should not be egotistical about their finances. I’m guilty of doing this back in the day. Now, though, I don’t let anyone know my financial affairs, unless I am required to disclose my positions. For the retail investor who doesn’t have time to scrutinize financial reports of companies or track the activities of these companies, a safe index fund is a great choice.